Litigation risk analysis in Wiersholm

The litigation risk is vital when choosing the right dispute strategy. Litigation risk analysis is therefore an important part of the dispute lawyer’s job. But how is it done in practice?

The litigation risk is vital when choosing the right dispute strategy. Is it worth the money to institute legal proceedings? Should the opponent’s settlement offer be accepted? Clients must together with their lawyers consider a number of strategic alternatives, which in most cases will be based on an understanding of litigation risk.

The many elements of uncertainty and the fact that they are of a legal as well as a factual nature, make it difficult to assess litigation risk. For example, the lawyer does not know exactly what the opponent will be submitting or what the principal witness will be saying when taking the stand. Moreover, the lawyer is not thoroughly familiar with the judges’ background experience and previous knowledge.

Tempting to back away

Because litigation risk is difficult to estimate, it is tempting for lawyers to back away from the question or to express themselves as diplomatically and irrefutably as possible – that way they will at least not be wrong! But failure to conduct a litigation risk assessment may prevent a sensible settlement of a dispute. If lawyers were better at making good litigation risk assessments early in the process, substantial resources could have been saved.

A useful tool when estimating as well as communicating litigation risk is the concept “expected value”. Advokat Øystein Myre Bremset described this concept (“litigation value”) in an article in Rett 24.

The basic premise is that a claim that is certain to succeed is worth more than a claim that is not certain to succeed. The expected value of a claim is equal to the summed-up products of the probability of the different outcomes of the dispute. If the claimant’s probability of being awarded NOK 1 000 000 is 75 percent and the probability of losing (and having to pay his own and the opponent’s expected legal costs of NOK 100 000 each) is 25 percent, the expected value will be (NOK 1 000 000 x 75 percent) – (200 000 x 25 percent) = NOK 700 000.

Such quantifiable presentations and analyses are, in our experience, useful tools for lawyers when giving their advice. Claims, legal costs, as well as settlement offers are valued in money. In the above example, the claimant should in principle accept all settlement offers exceeding NOK 700 000.

Settlement offer vs arguable claim

It is thus of little use to the client to be told that “the case is litigable” or that “it is more likely than not that the claim will succeed”. How can a specific settlement offer of NOK 400 000 be assessed against a “litigable” claim of NOK 1 000 000? It is impossible for the lawyer to give advice in this respect unless an expected value is estimated – even though this is often done implicitly (“accept the offer, the litigation risk is too high”).

Within the area of business law, we meet clients who in their day-to-day business are used to relating to a quantitative uncertainty. In many cases, there will not be just a single question of either – or, but a number of claims and issues in dispute. It is, for example, quite impossible to give good advice to a client in a major construction dispute involving numerous disputed claims without analysing the individual claims and estimating the expected value of the entire dispute.

Lawyer and poker player

Advokat Bremset has experience with the use of expected value and “pot odds” from his previous career as a poker player. The major difference between the lawyer and the poker player is the ability of the latter to with certainty distinguish a good hand from a bad hand (a pair of aces, for example, will always be better than one seven and one two).

The poker player cannot know the outcome of a hand, but if he has knowledge of mathematics, he may, for example, know that there is a 20 percent chance that the next card on the table will be exactly the card he needs to get an unbeatable hand (“nuts”) and can choose his strategy accordingly.

The lawyer’s assessment of a case outcome, on the other hand, depends on a number of legal and factual circumstances which are not mathematically quantifiable in the same way, and which are in themselves uncertain. The lawyer may estimate the probability of succeeding to be 65 percent, but, unlike the poker player, he does not know for certain whether the “cards” he has been dealt are good or bad, nor the exact probability of winning.

For the lawyer, even the uncertainty itself is uncertain. It is important to be aware of this fact when using quantitative methods such as calculation of probability and expected value.

Other considerations that are difficult to quantify

Expected value is a useful tool in cases where the advantages and disadvantages of an action can be measured in money. However, there are often other considerations that should also be taken into account in the litigation risk assessment, but which are not easy to quantify in the same way.

Firstly, the actual subject-matter in dispute may be difficult to quantify. The subject-matter of an action can, for example, concern an important test case where the consequences of succeeding or losing will have importance far beyond the specific case.

Secondly, all legal proceedings will be encumbered with costs (and profits) of a more indirect nature, such as reputation, custom relations or internal strain on the organisation.

Thirdly, liquidity considerations and a (rational) risk aversion will often make an amicable settlement preferable, even if the expected value, viewed separately, indicates that a court hearing would be wise. For example, most clients will rather accept a settlement proposal which in itself is poor than to risk bankruptcy, even if an average over time (which the expected value represents) viewed separately indicates that the risk is worth taking. In business, risk has a price, and that is something which the lawyer has to take into consideration when advising a client.

When assessing the litigation risk, it is important to understand what the client actually wants to achieve, and what interests are at stake. It is also important not to become hypnotised by the figures and lose the overall picture.

The importance of an analytic approach

Litigation risk assessments will always be uncertain, which makes it tempting to let one’s intuition decide. In our opinion, that is not a good idea. Even if it is not possible to determine the litigation risk with certainty, a thorough and analytic approach will give a better result than a decision based on the lawyer’s intuition.

Research has shown that lawyers are often wrong in their assessment of litigation risk. Sverre Blandhol has in an article in Lov og Rett 11/10 reviewed relevant research on this subject from the US.

The study «Let’s Not Make a Deal: An empirical Study of Decision Making in Unsuccessful Settlement Negotiations» (reviewed in Advokatbladet 5 – 2015) found that in more than sixty percent of the cases, the claimant was awarded the same amount as that offered prior to the hearing, or less. The study also revealed that women are better than men at assessing litigation risk.

In our opinion, there are several possible explanations why lawyers are often wrong in their assessment of litigation risk – in addition to the evident fact that it is difficult to find. One obvious explanation is the fact that lawyers do not make a sufficiently thorough and analytic assessment of the litigation risk; another reason for the erroneous assessments can be dognitive biases – which are, of course, also committed by lawyers.

Early overview of the facts and law – protection against confirmation bias

According to Sverre Blandhol’s article, one of the reasons for erroneous assessments of the litigation risk is the so-called confirmation bias. Confirmation bias means that humans have a clear tendency to seek evidence for what we already believe and ignore disconfirmatory evidence.

Lawyers are, in our opinion, particularly exposed to confirmation bias, perhaps in combination with a good portion of over-confidence. Our job is indeed to hunt high and low for everything that speaks in favour of our clients. Confirmation bias cannot be “switched off”. Instead, it is important that lawyers are conscious about the cognitive biases that exist and have a systematic approach that counters these to the extent possible.

Lawyers must initiate all litigation risk analyses by collecting the facts of the case and then structure and review these facts. The same applies to the work on legal sources, which should be done in a structured and systematic way. The lawyer should leave the conclusion of what is the “correct story” and correct law until all details of the course of events and the legal sources have been clarified and understood.

More specifically, the key to a “correct” review of the facts is, firstly, that the collection is arranged in a strictly chronological order. A course of events always takes place “in a space of time” and must therefore be investigated “in a space of time”. One incident leads to another, which again leads to the next. If the lawyer, for example, tries to arrange the case thematically, he risks missing crucial nuances and connections. It is said that “the devil is in the details” – the very first requirement must then be to find them!

The entire team must know all facts

Secondly, the collection and review of facts must take place in a way that at all times gives the rest of the team access to all the facts. It is not enough that one lawyer on the team knows all the facts – for a good litigation risk analysis to be made, the entire team must have this knowledge. A matrix of facts into which all documentation with comments is entered, is a useful tool. In Wiersholm, this is mandatory in all dispute cases.

Thirdly, discipline is important throughout the preparation of the case. When, for example, the opponent submits new documents with the reply, it is crucial that these documents are not reviewed in isolation. New bits of facts must be woven into the chronological “database” that has been built up. It must then be assessed whether the new bits contradict previous assessments of the facts. If that is the case, the lawyers must analyse whether this will be of importance to the litigation risk assessment.

Analytic litigation risk assessment in practice

When the factual and legal aspects of the case have been established to the extent possible, the lawyer must start working on the actual litigation risk analysis. In this phase, it is, in our opinion, important to prepare for a structured process ensuring that all arguments for and against are put forward, that conclusions are not drawn too early and that efforts are made to avoid the risks of, among other things, group think.

Group think means that assessments and decisions in groups are driven by a wish for harmony and agreement (conformity) within the group, rather than by realistic assessments of alternatives, often with the consequence that poor decisions are made.

There is no set answer to how such a structured process should be designed, but we believe the following three practical elements are important:

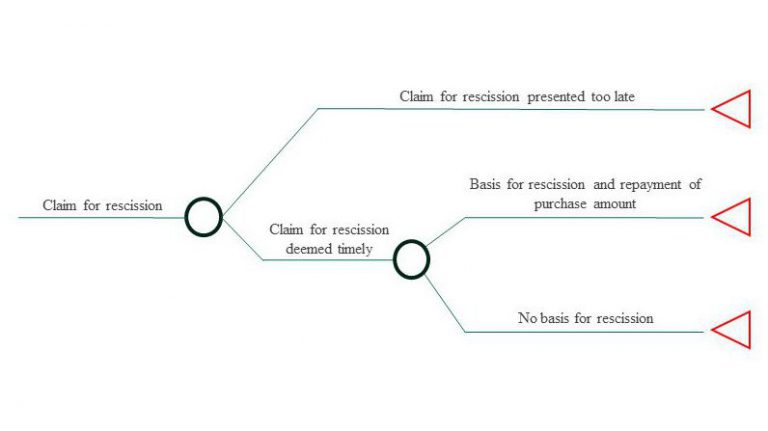

Firstly, the identified issues in dispute (“risk issues”) should be visualised by means of a decision tree or other similar tools. A decision tree gives both lawyer and client an overview of possible outcomes depending on the judge’s conclusions on the various issues in dispute, and does also serve as an excellent basis of discussion. A simple decision tree in a “rescission case” can look like the following:

Example of decision tree. Illustration: Wiersholm

Secondly, all members of the team should force themselves to try to postpone their conclusions regarding possible outcome for as long as possible. A method we use is to make a list of pros & cons for each issue in dispute without making any conclusion.

Finally, when all arguments for and against are on the table, all lawyers on the team (and possibly also the client) should be forced to “blindly” indicate a likely outcome of each issue in dispute (blinding).

Blinding means in practice that each lawyer on the team is forced to make his/her own assessment as to what will be a likely outcome without knowing what the others mean. This is simple, but very efficient.

The different assessments of the possible outcome are compared in subsequent plenary discussions. If possible, one member of the team should be appointed as the “devil’s advocate” with the clear role of challenging the viewpoints and arguments put forward by the rest of the team. Differences in the probability assessment are then discussed before a final conclusion is reached.

This being done, one can enter the estimated percentage probability of success for each issue in dispute and then estimate the compound probability for the claim. If estimating an 80 percent probability that the court will find that the complaint was made in time, but only a 50 percent probability that there is “material breach”, the probability of success in the claim for rescission will be 80 percent x 50 percent = 40 percent.

If the amount of the rescission claim is NOK 1 000 000, the expected value (exclusive of legal costs) will be NOK 400 000. Having performed this procedure, one may test the final result against one’s intuition. If there are large discrepancies, the claim should be analysed further.

More disputes can be amicably settled

When determining the strategy in a dispute case, this should be based on a thorough litigation risk assessment. If the lawyers on both sides of a dispute case at an early stage would make thorough litigation risk assessments along the lines we have presented in this article, we believe that more disputes would be amicably settled at an earlier stage.